Why does crafting good questions matter?

Creating/designing effective questions for students is one of the most common and powerful pedagogical strategies used by teachers during the process of teaching and learning. Good questions can benefit both teachers and students.

Reinhart (2000) states that questions can…

Reinhart (2000) states that questions can…

- For teachers:

- support teacher decisions.

- encourage students’ participation.

- communicate to students that their thinking is valued.

- show students initial knowledge.

- reveal students’ misconceptions.

- make them learn a new thing about their students.

- review previous topics.

- access understanding and curriculum goals.

- maintain the flow of the learning within the lesson.

- foster speculation, hypothesis, and idea/opinion forming.

- create a sense of shared learning and avoid the feel of a ‘lecture’.

- model higher-order thinking using examples and building on the responses of students.

- For students:

- help students articulate their thinking.

- generate critical thinking and inquiring behaviors.

- teach students to develop metacognition about a topic.

- develop students’ ability and repertory to formulate their own questions.

- improve high-level thinking and deep learning.

- promote insights and connections between areas.

What makes a question a “good” one?

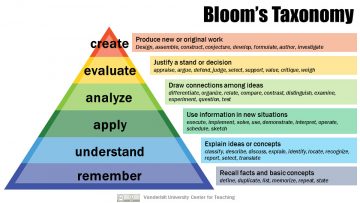

According to Bloom’s Taxonomy, the process of teaching and learning can develop different levels of thinking in students. In this sense, teachers can incentivize students to use lower or higher cognitive levels of thinking based on the teacher’s pedagogical goals. Therefore, it does not mean that teachers can never use the low levels since a lot of times teachers need to scaffold students’ skills. However, it is essential teachers analyze when, how, and why to use each level.

Source: Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

In terms of making questions, while lower levels of questioning access only students’ memory, high-level questions demand that students make connections, bring evidence, and even infer new knowledge.

If you are looking for more examples of questions in different levels or how to use them in your classroom using Bloom’s Taxonomy, there are many resources that you can use:

You can also see in the following video how teacher Melanie Agnew develops higher-level understanding through effective questioning in her High School English classes:

Guide for planning classroom questioning

Teachers know how many things can happen during a lesson and that is the reason that planning each moment or intervention is essential to promoting students’ engagement and learning. Thinking about the challenges that are to using questions in the classroom, the Center for Innovation in Teaching & Learning of the University of Illinois discusses some steps to successfully make questions in the classroom.

Cotton (1988) also gives some guidelines for classroom questioning:

- “Incorporate questioning into classroom teaching/learning practices.

- Ask questions that focus on the salient elements in the lesson; avoid questioning students about extraneous matters.

- When teaching students factual material, keep up a brisk instructional pace, frequently posing lower cognitive questions.

- With older and higher ability students, ask questions before (as well as after) material is read and studied.

- Question younger and lower ability students only after the material have been read and studied.

- Ask a majority of lower cognitive questions when instructing younger and lower ability students. Structure these questions so that most of them will elicit correct responses.

- Ask a majority of higher cognitive questions when instructing older and higher ability students.

- In settings where higher cognitive questions are appropriate, teach students strategies for drawing inferences.

- Keep wait time to about three seconds when conducting recitations involving a majority of lower cognitive questions.

- Increase wait time beyond three seconds when asking higher cognitive questions.

- Be particularly careful to allow generous amounts of wait-time to students perceived as having lower ability.

- Use redirection and probing as part of classroom questioning and keep these focused on salient elements of students’ responses.

- Avoid vague or critical responses to student answers during recitations.

- During recitations, use praise sparingly and make certain it is sincere, credible, and directly connected to the students’ responses” (p.8-9).

What does questioning look like in each content area?

If you are looking for different ways of making questions in each subject area, you can see these specific tips:

References:

Armstrong, P. (2010). Bloom’s Taxonomy. Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching. Retrieved May 5, 2022, from https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/blooms-taxonomy/.

Cotton, K. (1988). Classroom questioning. School improvement research series, 5, 1-22.

Reinhart, S. C. (2000). Never say anything a kid can say!. Mathematics teaching in the middle school, 5(8), 478-483.

Guest post by Peer Tutor Ariane Faria dos Santos (Ph.D. EDCP), May. 2022.